|

|

Continue reading ETI Views and News at

econtech.com,

or download a

printer-friendly version.

Follow us on Twitter @EconAndTech

|

|

Redefining "broadband" and constructing a new market reality

|

|

In March 2010, and with considerable fanfare, the FCC released its blueprint for universal broadband – the "National Broadband Plan" ("NBP"). The NBP set out as a national goal to "[e]nsure universal access to broadband network services" by creating "the Connect America Fund (CAF) to support the provision of affordable broadband and voice with at least 4 Mbps actual download speeds and shift up to $15.5 billion over the next decade from the existing Universal Service Fund (USF) program to support broadband." For many years, policymakers had defined "broadband" as a service providing a data rate of at least 200 kpbs in at least one direction. So the notion of a minimum threshold for "broadband" of 4 mpbs was certainly seen as a step in the right direction. But by the standards of 2012 – just two years after the FCC's Plan was published – 4 mbps seems rather pedestrian.

In March 2010, and with considerable fanfare, the FCC released its blueprint for universal broadband – the "National Broadband Plan" ("NBP"). The NBP set out as a national goal to "[e]nsure universal access to broadband network services" by creating "the Connect America Fund (CAF) to support the provision of affordable broadband and voice with at least 4 Mbps actual download speeds and shift up to $15.5 billion over the next decade from the existing Universal Service Fund (USF) program to support broadband." For many years, policymakers had defined "broadband" as a service providing a data rate of at least 200 kpbs in at least one direction. So the notion of a minimum threshold for "broadband" of 4 mpbs was certainly seen as a step in the right direction. But by the standards of 2012 – just two years after the FCC's Plan was published – 4 mbps seems rather pedestrian.

A lot has happened since 2010. Way back then, most video downloads consisted of relatively short low-definition clips from sites such as YouTube; real-time streaming of feature-length high definition movies and other video content was just beginning to emerge. Video chat services were generally confined to low definition, small "webcam" based images such as those provided using Skype and Google chat. Apple had yet to introduce the iPad 2 and iPhone 4, both of which were required for its new FaceTime video chat app.

Fixed – as distinct from mobile – broadband Internet access was being provided mainly by the local cable TV operator and by the incumbent local exchange carrier (ILEC). With the exception of areas falling within Verizon's FiOS footprint, cable generally offered higher speed services, but the need for these higher speeds had yet to materialize, so most consumers tended to view the two alternative providers as offering roughly equivalent services. Without defining specifically what constituted "broadband," the FCCs National Broadband Plan reported that "[a]pproximately 4% of housing units are in areas with three wireline providers (either DSL or fiber, the cable incumbent and a cable over-builder), 78% are in areas with two wireline providers, about 13% are in areas with a single wireline provider and 5% have no wireline provider." The FCC's conclusion: For the most part, the US fixed broadband market is competitive.

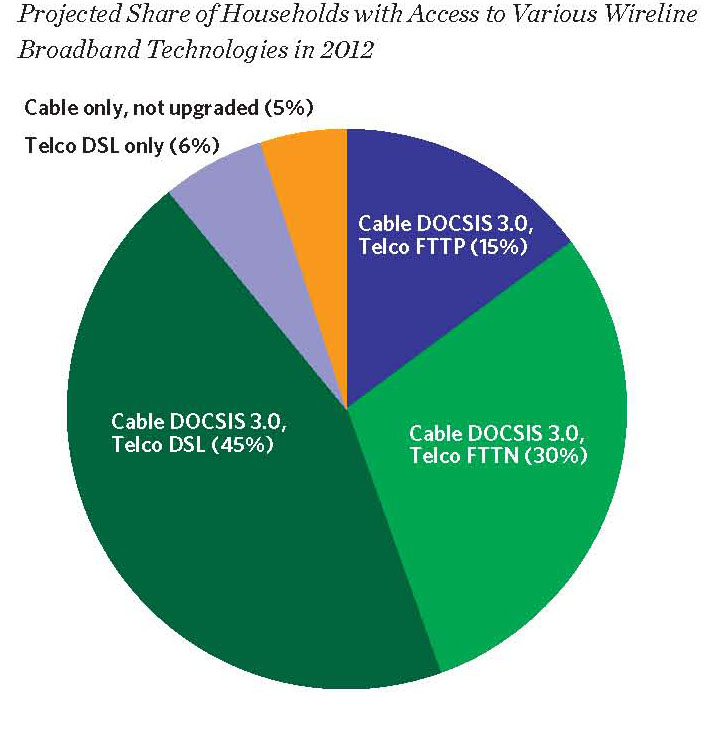

At the same time, the NBP did recognize that over time the need and thus the demand for higher speed broadband access would increase, and that perhaps under those (future) conditions a larger share of the population would be relegated to a single provider. The FCC classified ILEC broadband into three categories – telco DSL, telco Fiber-to-the-Node (FTTN), and telco Fiber-to-the-Premises(FTTP). DSL technology has been around for nearly twenty years, although it did not become available commercially until the late 1990s. DSL supports download/upload speeds of up to 3 mbps/768 kpbs, but is usually much slower. DSL speeds deteriorate rapidly when the distance between the subscriber and the telco wire center is longer than a mile or so. Telco FTTN is a version of DSL in which the critical length of the copper segment is reduced by extending fiber to "nodes" located in residential neighborhoods. AT&T's u-Verse broadband service is based upon an FTTN architecture. Cable broadband also uses an FTTN architecture, but the "last mile" link uses coaxial cable rather than twisted pair copper. Coax is capable of supporting far greater data rates. Verizon's FiOS uses an FTTP (sometimes referred to as FTTH – Fiber-to-the-Home) design. Cable broadband using the DOCSIS 3.0 standard is capable of data rates of 25 mbps, 50 mbps or even higher speeds fully comparable to FTTP and leaving FTTN and DSL in the dust. Most of the "competition" that the FCC had identified was between cable and one of the much shower telco "broadband" offerings – DSL or FTTN. As consumer demand for higher-speed services grows, the competitiveness of these slower telco offerings will diminish.

And the winner is ....

Cable has clearly emerged as the winner in the telco/cable broadband competition. Except for the 18-million or so homes passed by FiOS infrastructure, telco broadband cannot compete in the speed contest going forward. Verizon discontinued further expansion of its FiOS service after 2010 (Views and News, July 2012) because the investment did not prove successful financially, and in non-FiOS areas Verizon's "broadband" service is limited to DSL. AT&T has eschewed FTTP altogether in favor of a far less ambitious investment program in Fiber-to-the-Node, but as a result AT&T cannot offer transmission rates comparable to those available from the cableco.

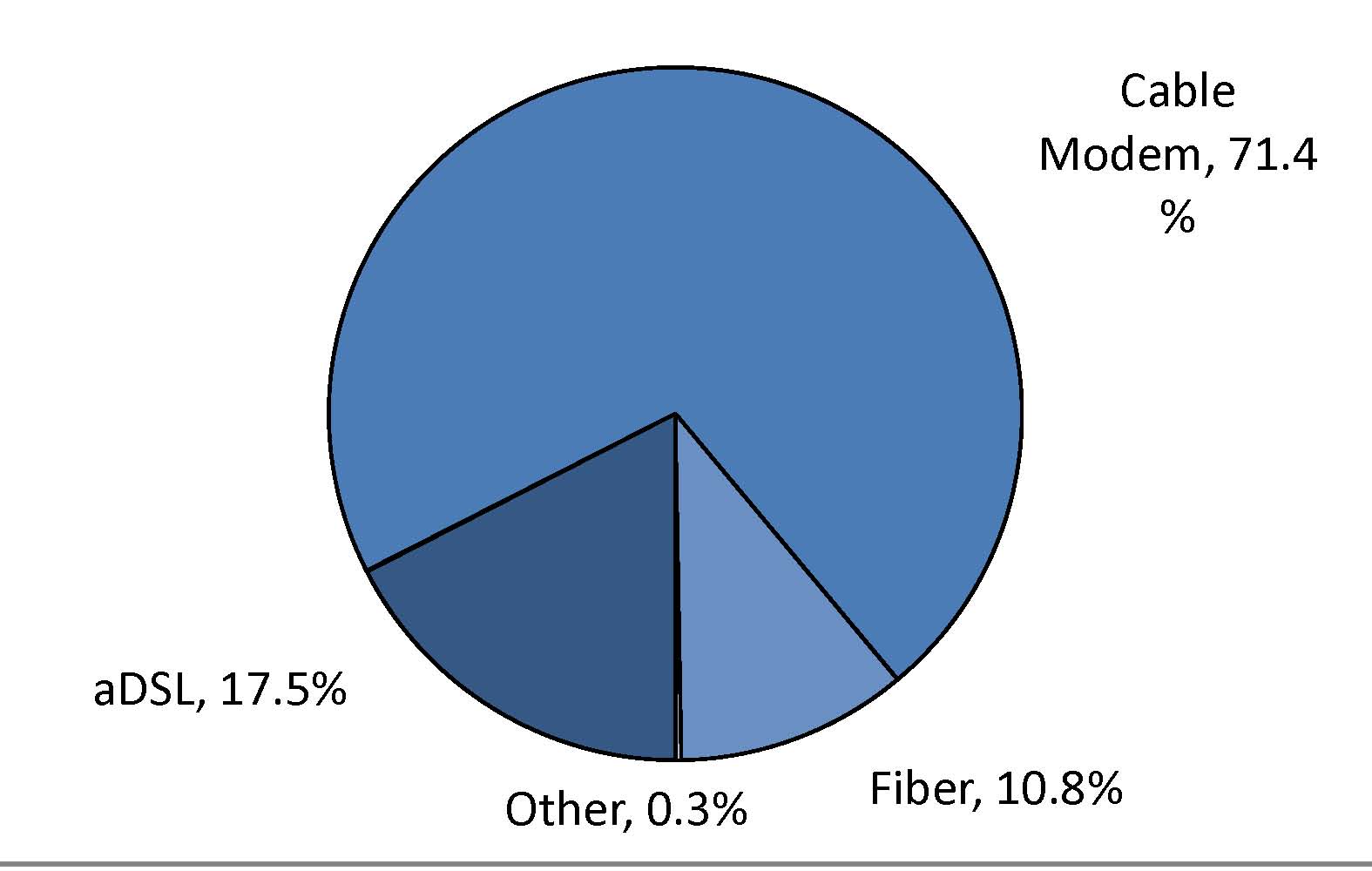

Data just issued by the FCC shows that cable holds a whopping 71.4% market share of residential fixed broadband connections of at least 3 mbps in the downstream direction, while competition from DSL (which can barely qualify to meet the 3 mbps threshold) holds only 17.5% share. Fiber startups (including Verizon FiOS) have only managed to capture 11% of the market. (See figure above.)

Data just issued by the FCC shows that cable holds a whopping 71.4% market share of residential fixed broadband connections of at least 3 mbps in the downstream direction, while competition from DSL (which can barely qualify to meet the 3 mbps threshold) holds only 17.5% share. Fiber startups (including Verizon FiOS) have only managed to capture 11% of the market. (See figure above.)

Having abandoned its plans for further expansion of FiOS, Verizon, so it now seems, has conceded defeat in the contest with cable. In a deal that received Justice Department blessing earlier this month, Verizon will start offering cable-based Internet access wherever it is not providing FiOS. As part of a $3.9-billion deal to purchase AWS spectrum from Comcast, Time Warner Cable, Bright House Networks, and Cox, Verizon will market (and presumably rebrand) these companies' broadband Internet access and video services as part of wireline telephone and wireless voice/data bundles. Just as the Betamax/VHS format war ended when Sony threw in the towel and started selling VHS machines, it would seem that the ILECs – and the FCC and the Department of Justice – have now concluded that in the battle for broadband it's time to declare cable the victor. Having acquired the ability to market cable broadband and video, telcos will now have little incentive to invest in their own broadband infrastructure, which means that there will, in the end, be only a single broadband "pipe" into most US homes.

The irony here is that for years the ILECs had argued that requiring them to provide CLECs with access to ILEC network elements would discourage CLEC investment, that the only real competition required facilities-based business models. Those arguments prevailed, and led to the DC Circuit Court's 2004 ruling relieving ILECs of the requirement to provide the Unbundled Network Element Platform ("UNE-P") to competing local carriers. It would appear that when it comes to their own strategy for entering new markets, the ILECs seem entirely comfortable with resale. Significantly, several key FCC rulings in the mid-2000s – the Cable Modem Order and the Broadband Wireline Internet Access Order – relieve both cable MSOs and ILECs of any requirement to offer wholesale broadband access to competing Internet access providers. So while the various cable participants in the Verizon deal will allow Verizon to repackage and resell their services, they are under no obligation to offer similar arrangements to anyone else.

Oh, well ...

What's less clear – and far more disturbing – is that the policymakers still seem to believe that the broadband market is competitive and that it can continue to be treated as an "information service" not subject to traditional common carrier regulation. While effectively bringing further telco broadband investment to an end, the FCC and DoJ remain in denial as to the demise of competition in this sector. If, as now seems to be the case, we end up with a single broadband provider in most parts of the country, the nation can't continue to treat those regional monopolies as if their pricing and conduct are constrained by competition. The FCC's approval last year of the Comcast/NBCU merger, putting the cable/broadband monopoly in control of a major content provider, only compounds the problem and the risks. While ETI continues to believe that DoJ and FCC approval of the Verizon/cable cross-marketing deal is both misguided and premature, if that's where these agencies want to take us, they need also to reconsider their longstanding vision of a deregulated competitive broadband marketplace and adopt regulatory measures consistent with the market reality they have chosen to create.

For more information, contact Lee L. Selwyn at lselwyn@econtech.com

Read the rest of Views and News, August 2012.

|

|

|

|

About ETI. Founded in 1972, Economics and Technology, Inc. is a leading research and consulting firm specializing in telecommunications regulation and policy, litigation support, taxation, service procurement, and negotiation. ETI serves a wide range of telecom industry stakeholders in the US and abroad, including telecommunications carriers, attorneys and their clients, consumer advocates, state and local governments, regulatory agencies, and large corporate, institutional and government purchasers of telecom services. |

|

|