Continue reading ETI Views and News at

econtech.com,

or download a

printer-friendly version.

Follow us on Twitter @EconAndTech

|

|

Intercarrier compensation in the Internet world: Charging content providers and content delivery networks for access to end users

|

|

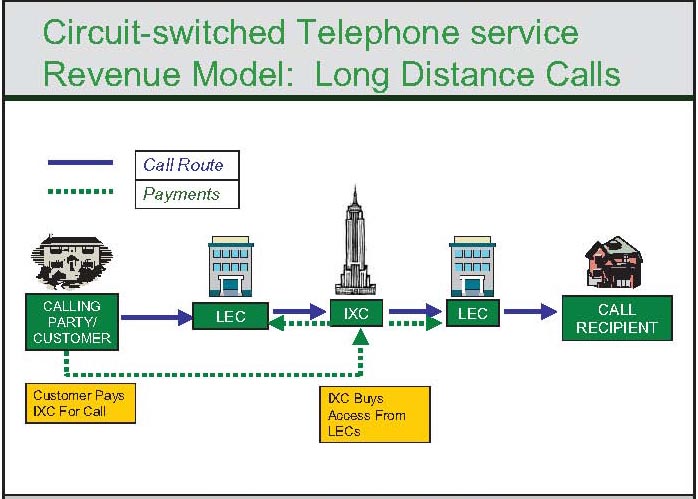

Ordinary local and long distance telephone calls often require the involvement of several different telecommunications carriers. This might occur, in the case of a local call, when the calling and called parties are served by different telephone companies. In the case of a long distance call, a third "interexchange" carrier ("IXC") may also be involved, to transport the call between the two local carriers where they do not directly interconnect with each other. For traditional switched telephone calls, one party – usually the caller but in some cases, such as for 800-type "toll-free" services, the called party, pays for the entire call. Thus, with all of the revenue being realized by one carrier while the services of one or more other carriers may be required to complete the call, some process is needed to assure that all of the carriers involved in providing the end-to-end connection receive compensation for their respective work.

Ordinary local and long distance telephone calls often require the involvement of several different telecommunications carriers. This might occur, in the case of a local call, when the calling and called parties are served by different telephone companies. In the case of a long distance call, a third "interexchange" carrier ("IXC") may also be involved, to transport the call between the two local carriers where they do not directly interconnect with each other. For traditional switched telephone calls, one party – usually the caller but in some cases, such as for 800-type "toll-free" services, the called party, pays for the entire call. Thus, with all of the revenue being realized by one carrier while the services of one or more other carriers may be required to complete the call, some process is needed to assure that all of the carriers involved in providing the end-to-end connection receive compensation for their respective work.

The term-of-art for such revenue-sharing arrangements is "intercarrier compensation." Prior to the mid-1990s’ arrival of competitive local exchange carriers ("CLECs"), situations where a local call involved the services of more than one incumbent local exchange carrier ("ILEC") were confined mainly to "extended area service" local calls between customers served by different ILECs whose operating territories were non-overlapping. In such cases, aggregate traffic flows in each direction over such intercarrier routes were roughly equal, and were considered to be "in balance." Where traffic was in balance, the connecting carriers generally operated under a "bill-and-keep" compensation arrangement – each carrier would keep all of the revenue it received for such intercarrier calls and agree to complete incoming calls handed-off to it by the other on a no-charge basis. Because CLEC and ILEC serving areas overlap and CLECs often specialize in serving certain types of customers, CLEC-ILEC traffic flows may not be balanced and, for that reason, one or both carriers may be reluctant to agree to a bill-and-keep compensation scheme.

Payment for long distance calls is typically made to the IXC, which in turn makes "access charge" payments to the calling and called parties’ respective local carriers for their work in originating and terminating the call. However, in addition to providing a device for revenue sharing, access charges – at least when first introduced in the mid-1980s – served the additional purpose of flowing revenues from long distance calling to subsidize basic residential access.

Prior to the 1984 break-up of (the old) AT&T, long distance rates had been set at multiples of cost, with the profits being used to defray the revenue shortfall associated with basic residential phone service, which public policy dictated be priced below cost as a means for encouraging universal connectivity. Access charges, like the long distance revenues they replaced, were also set at multiples of cost, with the excess similarly used to maintain the below-cost pricing of residential local service.

Click to enlarge.

When most of the nation’s local and long distance phone services were provided by (the old) AT&T prior to the onset of competition, intercarrier compensation was largely a matter of intracorporate accounting transfers among the various operating units within AT&T. Exchange of local traffic between AT&T and non-AT&T operating telcos was accomplished mainly on a bill-and-keep basis. Regulatory involvement was for the most part limited to "settlements" among Bell and non-Bell carriers with respect to intercarrier long distance traffic, and even there much of this was accomplished via direct industry negotiations. However, from the late 1970s on, intercarrier compensation between incumbent and competitive carriers – first long distance, then local as well – has remained one of the most controversial areas of federal and state regulatory activity.

When most of the nation’s local and long distance phone services were provided by (the old) AT&T prior to the onset of competition, intercarrier compensation was largely a matter of intracorporate accounting transfers among the various operating units within AT&T. Exchange of local traffic between AT&T and non-AT&T operating telcos was accomplished mainly on a bill-and-keep basis. Regulatory involvement was for the most part limited to "settlements" among Bell and non-Bell carriers with respect to intercarrier long distance traffic, and even there much of this was accomplished via direct industry negotiations. However, from the late 1970s on, intercarrier compensation between incumbent and competitive carriers – first long distance, then local as well – has remained one of the most controversial areas of federal and state regulatory activity.

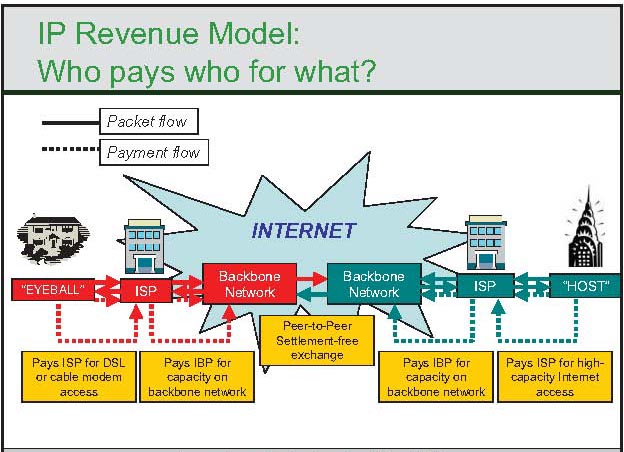

Internet traffic and revenue flows

The Internet grew up as a "network of networks" without any consequential regulatory involvement. Regional backbone carriers realized early on that interconnection and exchanges of traffic between and among their networks would increase the value of each and thus be mutually beneficial, and so without any regulatory prodding or prescription they negotiated bilateral "peering" arrangements governing their exchanges of inter-network traffic. End user access charges were not an issue, since users bought and paid for their Internet access from a local Internet Service Provider (ISP), initially on a dial-up basis, and later via a broadband service purchased either from the local phone or cable tv company. Unlike switched telephone service, in the Internet world all network users – consumers and host websites – were each responsible for obtaining and paying for the telecom link between their premises and the point within the Internet "cloud" where internetwork traffic would be exchanged, and for selecting and paying for the particular upload and download speeds they needed.

Click to enlarge.

Each individual Internet Backbone Provider ("IBP") established its own "peering policies" setting forth the conditions under which it would exchange traffic with another network on a no-fee (i.e., bill-and-keep) basis. While peering policies were not all identical, they generally had certain key features in common:

Each individual Internet Backbone Provider ("IBP") established its own "peering policies" setting forth the conditions under which it would exchange traffic with another network on a no-fee (i.e., bill-and-keep) basis. While peering policies were not all identical, they generally had certain key features in common:

- Traffic volumes at the peering point had to be roughly, but not exactly, in balance. In that regard, ratios of as much as 2:1 might still be considered as being sufficiently "in balance" to still qualify for a no-fee exchange.

- Traffic sent to the terminating network had to be destined for a point on that network; hand-offs made by the receiving network to a third network would be considered to be "transit traffic" and would not qualify for a no-fee exchange.

- The two participants in a peering arrangement both had to be large, so-called Tier I, backbone network providers. In general, the exchange of traffic between a backbone network and a local ISP’s distribution network would not qualify for no-fee traffic exchange. Instead, the local ISP would be required to purchase and pay for the long-haul transport from the backbone provider.

Voluntary peering arrangements emerged in the nascent Internet precisely because (1) such interconnections were beneficial to all of the participants, and (2) no one of the players extant at the time had market power sufficient to permit it to dictate terms to any of the others. In the dial-up Internet access era, where the ISP did not control the last-mile connection between its servers and its end user subscribers, the ISPs’ ability to leverage their relationships with those end users and to dictate terms to backbone network providers was all but nonexistent.

But all of that has changed. Cable and telco broadband ISPs own and control the last-mile link to their customers. Horizontal mergers and acquisitions have greatly expanded the geographic reach of the few remaining mega-firms – mainly AT&T, Verizon and Comcast. These firms are in the position to deliver – or to deny – third party content and other service providers the ability to reach tens of millions of end user "eyeballs" over which the ISPs maintain exclusive control.

The large ISPs are also positioned to protect their respective backbone network market by refusing to offer no-fee peering to smaller networks – particularly those that do not themselves operate at the retail consumer "eyeball" level. In fact, the FCC had recognized this potential as long as five years ago when, in granting its approval for the SBT/AT&T and Verizon/MCI mergers, it required that the number of pre-merger peering arrangements between these entities and unaffiliated backbone networks be maintained, albeit only temporarily. Those conditions have long since expired, and the prospects for peering and a competitive Internet backbone seem tenuous at best.

Comcast and Level 3: A case in point

The supply of Internet-delivered streaming video content has mushroomed in recent months, soaking up large swaths of Internet capacity while threatening traditional cable and ILEC TV content-based business models (see "De-linking Video Content from Video Delivery: Are Long-Standing Business Models Now at Risk?" ETI Views and News, November 2010). Netflix, in particular, has launched an ambitious effort at developing this market. In November, Netflix announced that it had entered into a contract with Level 3 under which the Tier I IBP would "serve as a primary content delivery network (CDN) provider for Netflix ... to support the company’s streaming functionality and to support storage for the entire Netflix library of content," and that "[a]s a result of the deal, Level 3 ... will double its storage capacity and add 2.9 Terabits per second (Tbps) of globally available CDN capacity, which is in addition to the 1.65 Tbps that was deployed in the third quarter of 2010." Under the arrangement, Level 3 will store copies of the Netflix film library at multiple sites around its network, and will deliver customer-bound traffic directly to the local broadband provider’s distribution network. As Level 3 describes it, this is not "peering" because there is no exchange of traffic between backbone networks; rather, this arrangement involves an interconnection between the local broadband distribution network and the source of the content.

Comcast, on the other hand, views its relationship with Level 3 entirely through the "peering" lens. Level 3 is sending Comcast considerably more traffic than Comcast is sending to Level 3, creating a massive traffic imbalance that is not permitted under Comcast’s no-fee peering policies. The problem with Comcast’s position, however, is that this is not a "peering" issue.

Peering arrangements were established among large Tier I IBPs none of which had any significant retail end user customers. ISPs did not "peer" with IBPs; rather, they purchased communications links into the Internet "cloud" from one or more IBPs. Comcast, like other ISPs, is paid by its end user customers for the Internet access that the ISP provides. That fee covers both the "last mile" link from the customer’s premises as well as the connection into the cloud, where the end user’s traffic is handed off to, or received from, other backbone networks. Customers are offered choices of bandwidth, so those with the greatest traffic demand will typically order the higher-priced, high-bandwidth levels of service. Since the end user already pays for the bandwidth he needs, a charge imposed by the ISP upon a CDN or other entity that delivers inbound traffic to the ISP’s customers amounts to charging twice for the same thing.

Comcast’s is imposing what amount to "access charges" upon Level 3 and its content-provider customers for the ability to reach Comcast’s end-user consumers. As the Commission appears to recognize (at para. 73 of its Open Internet inquiry), any actual, emerging, or potential competition for broadband Internet access services in the subscriber’s market simply becomes irrelevant for purposes of disciplining the provider’s behavior towards content, application, and service providers once the subscriber’s choice of access provider has been made, and with respect to any given consumer, third-party content providers and the CDNs they utilize are forced to deal with the end user consumer’s choice of ISP in order to communicate with that consumer. In fact, there is a direct and obvious parallel with a matter that the FCC had confronted nearly a decade ago, in its 2001 CLEC Access Charge Order. There, the Commission recognized that "IXCs are subject to the monopoly power that CLECs wield over access to their end user" and "given the unique nature of the market in which IXCs purchase CLEC access, ... we conclude that it is necessary to constrain the extent to which CLECs can exercise their monopoly power and recover an excessive share of their costs from their IXC access customers – and, through them, the long distance market generally." Similarly, the broadband Internet access provider takes on the role of gatekeeper with respect to the delivery of Internet traffic to its end user customers and, like those CLECs of the last decade, is in a position to exploit that relationship by imposing monopoly rents upon third-party content providers for access to its customers. It is unrealistic to rely upon arm’s length negotiations between the last mile broadband access provider and those seeking to communicate with its customers, because the parties to any such negotiation bring decidedly unequal market power to the table.

Finally, one must not overlook the potential for vertical market foreclosure in the ISP/CDN/content provider relationship. Cable and telco broadband service providers, in addition to offering high-speed Internet access, are the dominant incumbents with respect to video services that compete directly with Internet-delivered video content. In some cases these firms also have a major involvement in the content market itself (e.g., TimeWarner, Comcast). It has been argued that, despite these interrelationships, the nation’s antitrust laws are more than sufficient to address the potential for vertical foreclosure and other anticompetitive conduct. But such ex post antitrust remedies are simply not suited to the fast-paced Internet world; ex ante regulation, at least with respect to last mile access, is critical to preserving an open and competitive Internet.

If you would like more information on this subject, please contact Dr. Lee L. Selwyn.

Read the rest of Views and News, December 2010.

|

|

|

|

About ETI. Founded in 1972, Economics and Technology, Inc. is a leading research and consulting firm specializing in telecommunications regulation and policy, litigation support, taxation, service procurement, and negotiation. ETI serves a wide range of telecom industry stakeholders in the US and abroad, including telecommunications carriers, attorneys and their clients, consumer advocates, state and local governments, regulatory agencies, and large corporate, institutional and government purchasers of telecom services. |

|