|

|

Continue reading ETI Views and News at

econtech.com,

or download a

printer-friendly version.

Follow us on Twitter @EconAndTech

|

|

Verizon Communications to spin off its consumer wireline business?

|

|

Earlier this month, Bloomberg BusinessWeek described a recent Goldman Sachs research report in which the investment banking firm had suggested that Verizon should divest its fixed-line consumer operations so as to clear the way for the company to merge its wireless and enterprise units with UK partner Vodafone. In 2000, Vodaphone and then-Bell Atlantic both contributed their US wireless operations and assets to a joint venture to be called Cellco Partnership d/b/a Verizon Wireless. For its contributions to the venture, Vodaphone received 45% of Cellco, but Verizon Wireless and Vodafone's UK networks have remained separate.

Earlier this month, Bloomberg BusinessWeek described a recent Goldman Sachs research report in which the investment banking firm had suggested that Verizon should divest its fixed-line consumer operations so as to clear the way for the company to merge its wireless and enterprise units with UK partner Vodafone. In 2000, Vodaphone and then-Bell Atlantic both contributed their US wireless operations and assets to a joint venture to be called Cellco Partnership d/b/a Verizon Wireless. For its contributions to the venture, Vodaphone received 45% of Cellco, but Verizon Wireless and Vodafone's UK networks have remained separate.

Verizon has yet to comment on the Goldman recommendation, but there are a number of reasons why the company may well be considering such an initiative.

First, Verizon has already off-loaded a large chunk of its wireline operations. In 2008, it sold its Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont operations to Fairpoint Communications, Inc. and in 2005 sold its former-GTE Hawaiian Telecom to the Carlyle Group, a private equity firm. In 2010, Verizon sold a large portion of the wireline business it had acquired in its 2000 merger with GTE, along with the former Bell Atlantic's West Virginia operation, to Frontier Communications, Inc., retaining the three largest former-GTE markets in Florida, Texas and California. Immediately following the Bell Atlantic/GTE merger, Verizon was providing wireline service in some 28 state jurisdictions; that number is now down to only 12.

Verizon had been scaling back its investments in its traditional fixed line voice telephone business for some time, particularly in non-metropolitan markets. But in 2004 and with considerable fanfare, the Company announced an ambitious "fiber-to-the-home" (FTTH) broadband deployment branded as FiOS. FiOS investment was concentrated in Verizon's major east coast metropolitan markets; by 2010, the company had spent some $23-billion on the undertaking and had built out FiOS to some 18-million homes. FiOS penetration has remained relatively low, however. Verizon's 2010 10-K Report put the number of FiOS Internet subscribers at only 4-million and video subscribers at 3.5-million as of the end of that year, representing a per-subscriber investment of some $5,750 ($23-billion spread across 4-million subscribers).

The major cable multisystem operators (MSOs) like Comcast, TimeWarner Cable and Cox did not sit idly by while Verizon was in pursuit of the consumer broadband (and video) market. The MSOs were upgrading their systems by extending fiber deeper into residential neighborhoods and were implementing new transmission protocols like DOCSIS-3 that supported data rates on the MSOs' hybrid fiber/coax networks that rivaled what Verizon's FTTH architecture could achieve. In 2010, Verizon announced that it would call off all further expansion of FiOS beyond the 18-million homes that were to be passed as of the end of that year.

And Verizon's core wireline phone business was continuing to shrink. By the end of 2010, Verizon residential/small business access lines had dropped by 58%, from its 2000 peak of 63-million to 26-million.

The impact of wireless on wireline demand

Of course, a good deal of the drop-off in wireline demand was being offset by the immense growth of the wireless subscriber base. A large portion of that migration is likely attributable to Verizon's own marketing strategies. For much of the past decade, Verizon Wireless and most other US wireless carriers have eliminated the distinction between "local" and "long distance" calling. They offer "free" or nearly-free evening, night and weekend airtime, as well as "free" calling between mobile phones on their own networks and, more recently, between any US mobile phones. At the same time, wireline customers who had not subscribed for a long distance calling plan were being hit with ever increasing per-minute charges. It is no surprise that consumers got into the habit of placing long distance calls on their wireless phones and, in so doing, felt sufficiently comfortable with wireless that a good number (31% by the latest count) have "cut the cord" and eliminated their fixed wireline service altogether.

By virtue of its ownership and/or control of both consumer wireline and wireless services, Verizon was in a position to manage the "intermodal" rivalry between the two and to pursue a business strategy aimed at maximizing joint profits across the two platforms. The notion that Verizon's wireless service was somehow "competing" with its own wireline service is, to put it mildly, something of an overstatement.

A wireline divestiture

In principle, separating wireline and wireless into separate and truly competing companies could produce considerable competitive benefit. As a provider of both, Verizon has done little to enhance the attractiveness of its wireline services. It has retained the pricing distinction between "local" and "long distance" calling and has maintained what are by current standards absurdly small "local calling areas" of 20 miles or less despite the offering of what amounts to nationwide local calling by its own wireless affiliate. It persists in imposing additional charges for wireline "optional" features like call waiting, call forwarding, three-way calling, voice mail, call screening, and caller ID features that cost it little or nothing to provide while bundling these and others into its wireless pricing without any additional charge. On the other side, Verizon has worked to protect its FiOS investment by not upgrading its wireless network to offer comparable broadband and video services that could cannibalize the FiOS customer base (the latest LTE network upgrades offer download speeds that range from 1/5th of the slowest FiOS package, to 1/15th of the fastest).

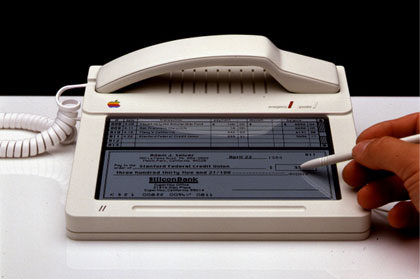

The prospect of the separation of Verizon's wireline and wireless operations offers the possibility that the two (then independent) companies would aggressively compete with each other for consumer business. There are, of course, limits to the direct substitution between the two services. Wireline phones are, by definition, tethered to a fixed location, whereas wireless phones are not. Hence, wireless is more of a substitute for wireline than vice versa. Nevertheless, for calls placed from the customer's home or other fixed location, wireline and wireless are substitutes. A wireline provider seeking to retain customers who might otherwise go wireless-only could certainly take measures to make the wireline service more attractive, such as by eliminating the local/long distance distinction and by bundling features with the service. It could offer more flexible call forwarding services, and speech-to-email voice mail, and could emphasize the far better voice quality and reliability of fixed line services in its marketing and advertising. Up to now, "smartphones" have largely been confined to mobile services, but fixed-line smartphones that could include easier-to-use keyboards, larger video displays, and that could support such features as multi-party video conferencing could well operate to stem the hemorrhaging of the wireline customer base. (Check out Apple's first smart telephone a landline from 1983, with integrated screen and computer.)

On the broadband side, a wireless provider that is not also in the wireline business could offer a serious challenge to fixed line broadband services like DSL and cable particularly in those areas where higher-speed services like FiOS are not available.

Is increased wireline/wireless competition a realistic expectation?

How likely are any of these to occur? A lot will depend upon what specific wireline assets Verizon actually divests, and the financial and technical strengths of the entity(ies) to whom the assets are sold. Goldman Sachs is urging that Verizon divest its consumer wireline assets, thus retaining those wireline assets it uses to serve large enterprise customers, along with all of its wireless assets. But it may not be that simple. A good deal of the network facilities that Verizon uses to serve large enterprise customers were acquired from MCI when the two firms merged in 2006. Those former-MCI assets form the core of what is known as the Verizon Business subsidiary of Verizon Communications. These assets are, in general, separate and distinct from, and not integrated with, the legacy Verizon local service network subscriber loops, remote terminals, central office switches, wire centers, and interoffice transport plant. However, services furnished to larger enterprise customers are not confined solely to the former MCI assets. If the purchaser of Verizon's consumer wireline business becomes the owner of all of these legacy local network facilities, then the remaining Verizon wireline business service unit will be required to purchase local access and transport from the divestee entity.

The situation is even more complex in the case of wireless. The true "wireless" portion of what are commonly referred to as "wireless services" is limited to just the "air segment" between the handheld wireless device and the nearest cell site. The connection between the cell site and the wireless switching office, and beyond that office to the rest of the public switched (local and long distance) network, consist almost entirely of wireline facilities. One category of those facilities the so-called "backhaul" links between each cell site and the wireless switching office are provided mainly by local exchange carriers. And where the wireless carrier is an affiliate of the local wireline incumbent local exchange carrier (ILEC), most or even all of those backhaul facilities are provided by the ILEC at all of the wireless affiliate's cell sites that lie within the ILEC's operating footprint. The interdependence of the wireless and wireline networks within a given geographic area cannot be overstated: There would be no wireless service without ILEC-provided wireline backhaul.

Wireless carriers obtain the use of the ILEC's backhaul facilities as "special access services" purchased from the ILEC pursuant to interstate special access tariffs or (if de-tariffed, as is the case in many areas) price lists. Non-ILEC-affiliated wireless carriers such as Sprint and TMobile obtain their backhaul facilities from the ILEC on the same basis as the ILEC-affiliated wireless carrier. Sprint (and T-Mobile as well, up until it announced plans to merge with AT&T) had been vociferous in their complaints about the excessive special access rates that they were being forced to pay to satisfy their backhaul needs. But as long as the affiliated wireless carriers like Verizon Wireless and AT&T Mobility were required to pay the same prices for these special access services as Sprint, the ILECs' rates were at least slightly constrained by their own affiliates' interests. Once Verizon Wireless's affiliation with (what would then be the former Verizon) ILEC is severed, backhaul rates could escalate even further. If Verizon and its Vodaphone partner are about to bet the farm on wireless, it seems difficult to imagine that they would willingly forgo control of these strategic backhaul assets.

Finding a weak divestee would be the likely solution

Can Verizon have its cake and eat it too? Perhaps. If history is any guide, Verizon has actually perfected a business model aimed at protecting its own strategic interests while still off-loading assets that no longer fit into its business plans. And Verizon has accomplished this with reasonable assurance that the buyer of these wireline assets will never pose a serious competitive challenge.

Verizon sold its three northern New England states to FairPoint, a small North Carolina-based independent telco whose pre-acquisition size (in terms of number of customers) was less than one-fifth that of the three-state operation it was acquiring. FairPoint ran into difficulty almost immediately. For some time prior to its sale, Verizon had paid little attention to its northern New England network. Upon taking over, FairPoint found itself with deteriorated plant badly in need of major capital infusions. Service quality deteriorated to the point where regulators in all three states convened a joint hearing with FairPoint management to demand solutions to the billing, service quality, and 911 issues plaguing consumers. FairPoint itself went into Chapter 11 in October 2009 and did not emerge from bankruptcy until January 2011. Customer complaints escalated, and the company experienced some of the largest line losses of any ILEC in the US.

Verizon sold its Hawaii ILEC to the Carlyle Group, a private equity firm that had made other telecom acquisitions but had never actually operated a large-scale ILEC entity. The Carlyle Group never successfully transitioned Hawaiian Tel over to its own operating platform, resulting in billing issues and extremely long hold times to reach customer service representatives. The company fired its CEO to bring in a turnaround specialist, only to end up filing for bankruptcy protection in 2008.

Verizon divested the majority of its former GTE ILEC operations along with the former Bell Atlantic West Virginia operation to Frontier Communications, a mid-sized independent rural telco that started out life as the ILEC serving Rochester, New York. Prior to the acquisition, Frontier served some 1.7-million subscriber lines; post-acquisition, that number mushroomed to 5.7-million. Verizon had done little to upgrade the former-GTE operations prior to the transaction, leaving the now-abandoned customers largely without broadband or anything more than the barest minimum DSL capability. How successful Frontier will be in accomplishing what Verizon had failed to do remains to be seen.

None of these divestitures involved any of the wireless assets owned or acquired from GTE that served these same geographic areas, belying the oft-stated claims of wireline/wireless synergy.

Regulators need to pay close attention to any proposed spin-off

When then-Bell Atlantic was in the process of taking over GTE back in 2000, it advanced claims of strong consumer benefits based upon the efficiencies of scale and scope that would result from the integration of the two companies' operations. Whatever the merits of such claims may have been at the time, it's difficult to imagine that state regulators in particular would have sanctioned the merger if they knew that what would become Verizon would balkanize its network into operating units smaller and financially weaker than had characterized the pre-merger Bell Atlantic and GTE. This situation is magnified by Verizon's strategic interest in retaining the lucrative special access portion of its networks across any divested geography, allowing the company to continue to serve high-profit enterprise customers and to protect Verizon Wireless backhaul, all while maintaining the excessive special access prices paid by its competitors.

For more information, contact Colin B. Weir at cweir@econtech.com

Read the rest of Views and News, January 2012.

|

|

|

|

About ETI. Founded in 1972, Economics and Technology, Inc. is a leading research and consulting firm specializing in telecommunications regulation and policy, litigation support, taxation, service procurement, and negotiation. ETI serves a wide range of telecom industry stakeholders in the US and abroad, including telecommunications carriers, attorneys and their clients, consumer advocates, state and local governments, regulatory agencies, and large corporate, institutional and government purchasers of telecom services. |

|

|